History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

The Dutch Golden Age

Holland occupied by France<

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

Holland occupied by France

Early in 1793 the French Republic declared war upon its northern neighbor, and during the winter of 1794-1795 the provinces were overrun - as those of the Austrian Netherlands had already been  and occupied. The stadholder was glad to escape to England on a fishing-smack. By the Treaty of The Hague, in 1795, the seven provinces were erected into a new nationality known as the Batavian Republic, whose leaders were clearly expected to take their orders from Paris. The constitution was overhauled and the stadholderate was abolished.

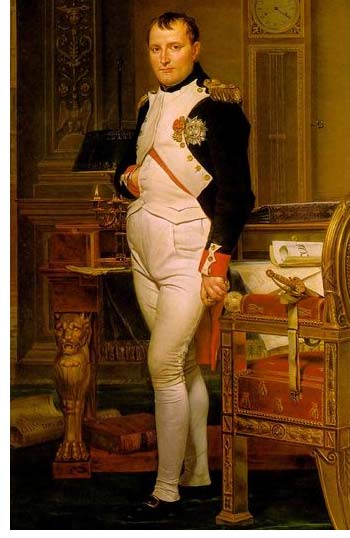

Early in 1793 the French Republic declared war upon its northern neighbor, and during the winter of 1794-1795 the provinces were overrun - as those of the Austrian Netherlands had already been  and occupied. The stadholder was glad to escape to England on a fishing-smack. By the Treaty of The Hague, in 1795, the seven provinces were erected into a new nationality known as the Batavian Republic, whose leaders were clearly expected to take their orders from Paris. The constitution was overhauled and the stadholderate was abolished.Thereafter there was not a phase of the experiences of Revolutionary France which was not reproduced more or less closely in Holland. Constitution followed constitution, and finally, in 1806, the Batavian Republic was converted by Napoleon into the Kingdom of Holland, and Louis Napoleon, brother of the emperor, was set up as the unwilling sovereign of an unwilling people.

Under great difficulties Louis sought for four years to rule his Dutch subjects in their own interest. The consequence was that he displeased his autocratic brother; and in 1810, under pressure, he abdicated. An imperial edict thereupon swept away what remained of Dutch independence and incorporated the provinces absolutely with France. The governmental system was altered upon French lines, and no effort was spared to obliterate every survival of Dutch nationality.

At the overthrow of Napoleon the situation of Holland was desperate. By taxation and in other ways she. had been robbed of her last penny. A generation of her young men had been practically annihilated as conscripts in the French armies. Her colonies were lost, her industries were broken up, and the last small remnants of her carrying trade had been captured by the English.

The people, however, had gained enormously in one respect. They has been hammered into a genuine nation and made to appreciate the advantages of a centralized government.

In November, 1813, as a part of the European uprising against Napoleon which followed the battle of Leipsic, a revolution broke out in Holland, and the French were expelled from the provinces. It was decided to turn for leadership to the national dynasty, and the son of the late stadholder, William V, was invited to return from England and put himself at the head of his countrymen. The invitation was accepted, and within a fortnight after the first outbreak at The Hague the prince landed at Scheveningen.

The final disposition of both the Dutch and the Belgian territories fell to the rulers and diplomats assembled in the Congress of Vienna. The decision of these self-appointed arbiters was to unite the two groups of provinces in a single state, to be known as the Kingdom of the Netherlands, with the Prince of Orange as sovereign.

The plan was carried into execution. Under the title of William I, the prince began his reign in March, 1815, and a constitution for the new monarchy, drafted by a commission consisting of an equal number of Dutch and Belgian members, was promulgated five months later. The principal object of the Allied Powers, especially England, was to bring into existence in the Low Countries a state which should be sufficiently strong to constitute a barrier against French aggressions upon the north.

In relation to Belgium, the statesmen who remapped Europe considered only the question whether the country should be given back to Austria or added to Holland. They had no thought of conceding it a position of independence. The separation of the two groups of provinces tied together at Vienna was, however, inevitable. Friction between the Dutch and Belgians was from the outset, and the king's honest, though of ten mistaken, efforts to bring about a genuine amalgamation only emphasized the irreconcilable differences of his subjects in language, religion, economic interest, and political inheritance.

In August, 1830, the Belgians broke into open revolt at Brussels. A hastily elected congress proclaimed the country's independence, a liberal constitution was adopted, and Leopold of Saxe-Coburg, under the title of Leopold I, was crowned king. A conference of the powers at London in 1831 drew up a treaty of separation, recognizing both the independence and the neutrality of the new Belgian monarchy; and although not until 1839 did King William sign this instrument, he was restrained from violating its terms.

The history of the Dutch kingdom since the achievement of Belgian independence has been placid. Although not neutralized by international agreement, the country had known no war, and the only disturbances of its political tranquillity had been caused by successive agitations for the liberalizing of its originally autocratic governmental system.

At various times, notably in 1848 and 1861, the constitution has been amended, until today the parliamentary system prevails almost as completely as in England or France. The two houses of the States General are both elective, and since 1897 the franchise has been broadly democratic. The country is organized in twelve provinces - North Holland, South Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, North Brabant, Limburg, Gelderland, Overijssel, Drenthe, Friesland, Groningen and Flevoland - each of which has a unicameral representative assembly with large powers of local legislation.

The crown is vested in the family of Orange-Nassau, which first became a royal house in Holland in 1814. The first sovereign was William I, who, disgusted by the circumstances which compelled him to acquiesce in the defection of his southern provinces, and chagrined by the constitutional changes to which the Liberal party compelled him to submit, abdicated in 1840. The second was his son William II, who ruled from 1840 to 1849. William II's son succeeded as William III, in 1849, and ruled until 1890. He was twice married, but his sons by his first wife, Sophia of Wuerttemberg, did not survive him, and his successor was his only daughter by his second wife, Emma of Waldeck-Pyrmont.

Queen Wilhelmina was born in 1880. In 1901 she became the wife of Prince Henry of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, generally called Prince Hendrik. A daughter, born in 1909 and christened Juliana - after her ancestress, Juliana of Stolberg, mother of William the Silent - was heiress to the crown.

Although Holland has no proclaimed capital, The Hague has always been the seat of the monarchy. There is the royal palace, built by Prince Frederick Henry of Orange, son of William the Silent; there also, in a suburban park, is the Huis ten Bosch (House in the Wood), which the queen and her consort use as a country residence. The life of the court is following the old customs.

Napoleon once referred to Holland contemptuously as the alluvion of French rivers. The larger part of the country was

originally, indeed, a vast swamp, and approximately one-half of it today lies on a level with the sea, or still lower.

Enormous transformations of the ragged coastÂline have taken place in historic times, among them the conversion of the expanse of water known as the Zuider Zee from an inland lake (nowadays IJsselmeer) into an arm of the ocean. This was chiefly due to great storms and inundations during the thirteenth century.

From the earliest times the inhabitants have fought the sea with dykes, and but for these constructions Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Delft, Haarlem, Dordrecht, Utrecht, and territory occupied by millions of people would disappear in the waves. There is much truth in the Dutch proverb that God made the sea, but man made the land. Under the conditions that surrounded them, the Dutch could not fail to become amphibious, a nation of fishermen and sailors. But if nature has been cruel to the Hollanders, it has also been kind. The remarkable material prosperity of the country, today as formerly, is attributable largely to the abundance of harbors, and to the far-stretching rivers that bring the trade of central Europe to Dutch ports. In volume of international commerce the country ranks high in the world, and Rotterdam is of the great seaports of the world.