History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture<

Renaissance period

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

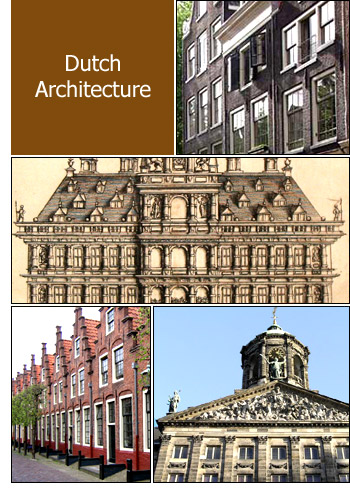

Dutch architecture

It is in the old towns of Holland that the architectural expression of the Dutch people is to be sought. Theirs was an intimate and human architecture, concerned with everyday events, and it developed out of the civil and domestic life. Many of the towns continue to be busy and prosperous, and new buildings here and there crowd in upon the picturesque groups of houses that for centuries have clustered round the great churches and market-places: in others, the active days of commerce are over, the merchants come no more, and the streets and waterways are quiet. But all Dutch towns having any pretension to age possess, to a wonderful degree, what may be termed an old-world atmosphere.

It is in the old towns of Holland that the architectural expression of the Dutch people is to be sought. Theirs was an intimate and human architecture, concerned with everyday events, and it developed out of the civil and domestic life. Many of the towns continue to be busy and prosperous, and new buildings here and there crowd in upon the picturesque groups of houses that for centuries have clustered round the great churches and market-places: in others, the active days of commerce are over, the merchants come no more, and the streets and waterways are quiet. But all Dutch towns having any pretension to age possess, to a wonderful degree, what may be termed an old-world atmosphere.Much of their charm, it is true, is due to the rivers and canals that encircle and intersect them in all directions, imparting a sense of quaintness and novelty; but it is the extraordinary number of old buildings still existing, unchanged in form since the days when they were erected and mellowed by ages of sun and rain, that ever appeal to the eye and imagination. The fantastic gables and red roofs, above which rise slender spires and belfries surmounted by leaden fleches and wrought vanes, together with the waterways and canal life, the windmills, and changing skies, are as characteristic now as when the masters of the great Dutch School of painting were living and, working.

Such scenes were to them inspiration; to picture the intimate events associated was their delight. If the painters have gone and with them the arquebusiers and governors and burgomasters - the gables, the sunlit courts, and many other familiar features remain.

The peculiar geographical conditions that have always existed in Holland have affected in no small degree the development of the land and the temperament of the people. Most of the country is below sea level. Behind the dunes and dykes the sea threatens inundation; the fear ot accident by flood has kept the nation watchful and in perpetual war with its ancient enemy.

The influence of this natural check has been far-reaching. It has produced the system of canals, determined the character of the landscape, made accordant life and work, method, regularity and order, and brought philosophy and fortitude to the national mind. In the domain of building, as in other spheres, water has been a powerful underlying agent affecting the evolution of style, just as the mountains, forests and deserts of other countries have imparted distinction to architecture.

Side by side with the external conditions imposed by Nature, conditions that, if accepted, might well be expected to have produced an attitude of extreme lack of initiative in those living amongst them, the Dutch have ever been an enterprising people. The same spirit that defied and conquered the inroads of the sea characterised their dealings in the domain of commerce. Trade was to them the great business of life. From very early times, and continuing for a long period, the prosperity of the Low Countries was toremost in Europe. The towns became centres of busy and pulsative life, the homes of virile civil and domestic communities. Many old buildings still existing, town halls, weigh houses, trade and guild halls, warehouses and merchants' premises, bear witness to those strenuous days.

To better appreciate the course of architectural development, it will be well to briefly cite the main circumstances connected with these towns and with the country's history. Records of Dutch towns prior to the twelfth century are scanty, although at that time orderly government had begun to develop. Then followed the municipal charters, many dating from the thirteenth century. These charters were granted by the feudal lords to the townspeople and secured to them certain rights and protection in return for taxation and levies; justice was administered by various governing bodies and magistrates, and the municipal finances were properly supervised. There thus grew up a strong communal movement which was steadily developed and strengthened.

Then it was that the cities began their era of great prosperity and each became practically self-governing and semi-independent. Revenue was derived from the river commerce and markets, over-sea trading, and from the industries which were fostered. So powerful did they become, so energetic was their municipal life, so well organised their trade, that these cities came to be reckoned, together with the neighbouring towns of Flanders, the most prosperous and wealthy in the world.

As time went on the chief cities became members of the Hanseatic League, which influential association embraced trading colonies in places as far apart as London, Visby on the island of Gotland, Novgorod the Great in Russia, Hamburg, Amsterdam and Kampen on the Zuider Zee. Through the impetus of this remarkable movement, the long-continued commercial relations between England and Holland were established. About the middle of the thirteenth century Hanse merchants settled in London, obtained privileges from Henry III, founded the Steelyard, and there developed a flourishing trade.

The intercourse between the two countries was very considerable, and it was of the utmost importance to the Netherlands that nothing should happen to weaken their good relations with England. For England was then the principal wool-producing country of Europe, the only place, in fact, able to supply it in large quantities, and the men of the Low Countries, famed above all for their skill as weavers and depending upon the woollen industry for their greatest wealth, were eager buyers of English wool in the raw state. In the fifteenth century, through dissension and war, the cities of Holland were ejected from the Hanseatic League; but the Dutch, with their fine ships and business acumen, continued to prosper and carried their conquests by trade into far-distant lands.

It was while at the height of their material success that the provinces of Holland came under the dominion of the house of Burgundy. The peculiar independent constitution of the cities promoted rivalry between them, rather than a common national interest which would have been best for the preservation of their just rights. They were heavily taxed and oppressed and were continually at variance with the ruling power, fighting for the redress of their grievances. By the first half of the sixteenth century the kingdom of the Netherlands had passed to the Emperor Charles V, King of Spain, and Philip, his son, inherited his father's throne. He thereby became monarch of vast territories. Philip determined to utterly subjugate the provinces and carried out a policy of relentless persecution. The people rebelled, brutal punishment followed, and they became victims of the worst excesses of the Inquisition. Deeds of cruelty, tyranny and murder were enacted. In those dark days arose that great champion of the people, "William the Silent," Prince of Orange, the "father of his fatherland."

Intent on defending the liberties of the nation, he gathered around him a company of gallant spirits, and, principally at his own expense, commenced what at first appeared to be a hopeless struggle. But early victories, hardly won, roused a cowed populace to action. The nation embarked upon the memorable Eighty Years' War, which resulted in the Spanish yoke being overthrown and the founding of the Dutch Republic. William was basely assassinated at Delft in 1584, and Maurits van Nassau (Maurice of Nassau), his second son, succeeded him as Stadtholder. He was ambitious, shrewd, and skilled in the arts of war, and under his rule, and that of his brother Frederick Henry, who succeeded him in 1625, the fortunes of the Dutch gradually rose high.

Through times of trial and suffering, hardships endured and conquests won, they emerged valorous and strong, a nation of heroes. Triumphs of arms by land and sea, successes of the merchant fleets and navigators who explored remote parts of the world, the founding of colonies, and ingenuity on the part of the workers in home manufactures, characterised a notable period of great prosperity; the Dutch became supreme in trade, chief rulers of the sea, and accumulated vast wealth.

As the seventeenth century advanced commercial welfare continued to increase. Admirals Tromp and De Ruyter swept the seas, gaining brilliant naval victories; in 1667 the safety of London itself was threatened by the appearance of the Dutch fleet in the Thames. But the mastery of the sea eventually passed to England and from that time the fortunes of the Dutch declined. The election of William III - who had married Princess Mary, daughter of the Duke of York to the English throne in 1689 marked the close of Holland's greatest days.

Early Dutch secular architecture is in the spirit of the late Gothic style. The most valuable monuments of that period are the civic buildings which herald a time when public life as opposed to ecclesiastical assumed an importance and dignity capable of being symbolized in brick and stone; when power acquired by trade found expression in its own distinctive forms, and the wealthy burghers of the towns erected municipal buildings which stand for all time as the embodiment of their ideals.

Such is the Town Hall at Middelburg by Ant. Keldermans the Younger, one of that famous family of architects of Malines. It is a stone erection of fine proportions, enriched with a wealth of detail, sculptured figures, sunk panelling and many turrets; tiers of dormers break up the roof surface and the whole is surmounted by a noble and boldly conceived tower. At Veere, not far distant, is a smaller example (opposite) built in 1474 by another member of the Keldermans family. While owning some similarity to its fellow at Middelburg, the treatment is simpler, but the proportions are exquisite, and the peculiar grace of the belfry is outstanding.

The characteristic richness of surface decoration which was then common may also be seen on the sandstone facade of the "Gemeenlandshuis" at Delft, with its elaborate traceries and parapet belonging to the early sixteenth century. The aforeÂmentioned are stone buildings and betray the influence of French Gothic, but the especially individual Netherlandish interpretation of Gothic was developed in the brick architecture. Brickwork was much employed and the nature of the material not so responsive as stone in the hands of the craftsmen limited the possibilities of ornamental treatment. Detail had to be simplified and adapted to the means available for carrying it out. It is in this early brickwork that the germs of the Dutch transitional Renaissance style are to be traced; its root principles were derived not only from the public buildings, but from the churches also vast piles whose bold masses and ornaments were logically developed out of the material, and whose millions of little bricks, jointed together, stand as impressive memorials of patient labour.

Medieval domestic work followed in the wake of the civic. Not many examples remain. Of those that have survived most belong to the late fifteenth or the first half of the sixteenth century. The current forms of the period were employed panelling and projecting surface decoration, more often in brickwork than stone; arched window-heads ornamented with tracery; circular brick turrets surmounted by conical roofs; stepped gables having pinnacles rising from the copings; steep roofs pierced by dormers; and the somewhat florid, rich, but carefully wrought detail.

In contrast to the scarcity of Gothic domestic buildings, those of the Transitional period from Gothic to Renaissance are very numerous. Many examples are to be found in the old towns where rows of houses, much out of the perpendicular, rise from the canalsides and paved roadways. They are narrow and very high and are surmounted by gables which are often of fantastic shape and curious outline, picturesque from the draughtsman's point of view and full of subject for the painter. Strange though it now seems, and quite beyond reasonable explanation, the greatest art movement that Holland has ever known flourished at the close of those troubloustimes when she was at war with Spain. It was then that the painters, with startling suddenness, came into their full powers, and Hals, Rembrandt, Van der Helst, Gerard Dou, Paul Potter, Jan Steen, Ruysdael and De Hooch, with a host of brilliant companions, followed in quick succession.

They created a new art, a school of painting with original conceptive views and unrivalled executive skill. Contemporaneously with this artistic activity developed the peculiarly specific Dutch style of domestic architecture. Existing examples prove how energetically the building craft was then carried on, and show how its characteristics were matured during the closing years of the sixteenth century and onwards through the century following. Many of the Town Halls and Weigh Houses, which set the fashion for the private dwellings, are of this time; Leiden 1598, Haarlem 1602, Nijmegen 1612, Bolsward 1614, Workum 1650, and numerous others.