History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

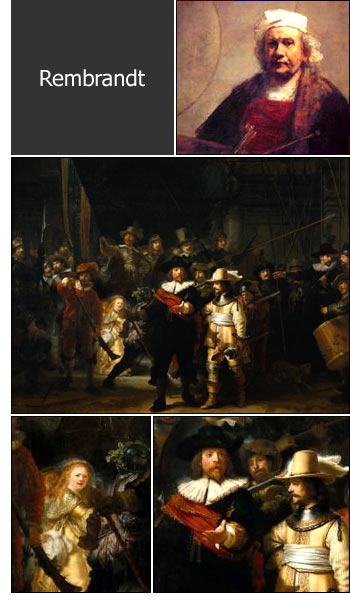

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch<

Rembrandt the artist

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

One writer has said that the great painter Rembrandt was born "in a windmill," but this is not true. He was born in Leyden for certain, though not a great deal is known about his youth; and his father was a miller, his mother a baker's daughter.

One writer has said that the great painter Rembrandt was born "in a windmill," but this is not true. He was born in Leyden for certain, though not a great deal is known about his youth; and his father was a miller, his mother a baker's daughter.Rembrandt was born at No. 3, Weddesteeg, a house on the rampart looking out upon the river Rhine whose two arms meet there. In front of it whirled the great arms of his father's windmill, though he was not born in it; and of all the women Rembrandt ever knew, it is not likely that he ever admired or loved one as passionately as he admired and loved his mother. He painted and etched her again and again, with a touch so tender that his deepest emotion is placed before us.

Rembrandt had brothers and sisters - five: Adriaen, Gerrit, Machteld, Cornelis, and Willem. Of these, Adriaen became a miller like his father, and presumably the old historic windmill fell to him; Willem became a baker, but Rembrandt, the fourth child, it was determined should be a learned man, and belong to one of the honoured professions, such as the law. So he was sent to the Leyden Academy, but here again we have an artist who decided he knew enough of all else but art before he was twelve years old. He found himself at that age in the studio of his first art-master, Jacob van Swanenburch, a relative, who had studied art in Italy, and was a good master for the lad; but Rembrandt became so brilliant a painter in three years' time, that he was sent to Amsterdam to learn of abler men.

The lad could not in those days get far from his adored mother; so he stayed only a little time, before he went back to Leyden where she was. There was his heart, and, painting or no painting, he must be near it.

Until the past thirty years no one has seemed to know a great deal of Rembrandt's early history, but much was written of him as a boorish, gross, vulgar fellow. Those stories were false. He was a devoted son, handsome, studious in art, and earnest in all that he did, and after he had made his first notable painting he was compelled by the demands of his work to move to Amsterdam for good. He hired an apartment over a shop on the Quay Bloemgracht; it is probable that his sister went with him to keep his house, and that it is her face repeated so frequently in the many pictures which he painted at that time. This does not suggest coarse doings or a careless life, but permits us to imagine a quiet, sober, unselfish existence for the young bachelor at that time.

Soon, however, he fell in love. He saw one other woman to place in his heart and memory beside his mother. His wife was Saskia van Ulenburg, the daughter of an aristocrat, refined and rich. He met her through her cousin, an art dealer, who had ordered Rembrandt to paint a portrait of his dainty cousin. Rembrandt could have been nothing but what was delightful and good, since he was loved by so charming a girl as Saskia.

He painted her sitting upon his knee, and used her as model in many pictures. First, last, and always he loved her tenderly.

In one portrait she is dressed in "red and gold-embroidered velvets"; the mantle she wore he had brought from Leyden. In another picture she is at her toilet, having her hair arranged; again she is painted in a great red velvet hat, and then as a Jewish bride, wearing pearls, and holding a shepherd's staff in her hand. Again, Rembrandt painted himself as a giant at the feet of a dainty woman, and in every way his work showed his love for her. After he married her, in June 1634, he painted the picture, "Samson's Wedding," "Saskia, dainty and serene, sitting like a princess in a circle of her relatives, he himself appearing as a crude plebeian, whose strange jokes frighten more than they amuse the distinguished company. The early years of his marriage were spent in joy and revelry. Surrounded by calculating business men who kept a tight grasp on their money bags, he assumed the role of an artist scattering money with a free hand; surrounded by small townsmen most proper in demeanour, he revealed himself as the bold lasquenet, frightening them by his cavalier manners. He brought together all manner of Oriental arms, ancient fabrics, and gleaming jewellery; and his house became one of the sights of Amsterdam." His existence reads like a fairy tale.

It is said that Saskia strutted about decked in gold and diamonds, till her relatives "shook their heads" in alarm and amazement at such wild goings on.

Before he married Saskia he had painted a remarkable picture, named the "School of Anatomy." It represents a great anatomist, the friend of Rembrandt - Nicholaus Tulp, - and a group of physicians who were members of the Guild of Surgeons of Amsterdam. It is so wonderful a picture that even the dead man, who is being used as a subject by the anatomist, does not too greatly disturb us as we look upon him. The thoughtful, interested faces of the surgeons are so strong that we half lose ourselves in their feeling, and forget to start in repulsion at sight of the dead body. A fine description of this painting can be found in Sarah K. Bolton's book "Famous Artists" and it includes the description given by another excellent authority.

The artist was twenty-six years old when he painted the "School of Anatomy." This picture is now at The Hague and two hundred years after it was painted the Dutch Government gave 30,000 florins for it.

Rembrandt painted a good many "Samsons" first and last - himself evidently being the strong man; and the pictures beyond doubt express his own mood and his idea of his relation to things. After a little son was born to the artist, he painted still another Samson - this time menacing his father-in-law but as the artist had named his son after his father-in-law, - Rombertus - we cannot believe that there was any menace in the heart of Rembrandt - Samson. Soon his son died, and Rembrandt thought he should never again know happiness, or that the world could hold a greater grief, but one day he was to learn otherwise. A little girl was born to the artist, named Cornelia, after Rembrandt's mother, and he was again very happy.

Meantime his brothers and sisters had died, and there came some trouble over Rembrandt's inheritance, but what angered him most of all, was that Saskia's relatives said she "had squandered her heritage in ornaments and ostentation." This made Rembrandt wild with rage, and he sued her slanderers, for he himself had done the squandering, buying every beautiful thing he could find or pay for, to deck Saskia in, and he meant to go on doing so.

At this time he painted a picture of "The Feast of Ahasuerus" (or the "Wedding of Samson") and he placed Saskia in the middle of the table to represent Esther or Delilah as the case might be, dressed in a way to horrify her critical relatives, for she looked like a veritable princess laden with gorgeous jewels.

One of his pictures he wished to have hung in a strong light, for he said: "Pictures are not made to be smelt. The odour of the colours is unhealthy."

The first baby girl died and on the birth of another daughter she too was named Cornelia, but that baby girl also died, and next came a son, Titus, named for Saskia's sister, Titia, and then Saskia died. Thus Rembrandt knew the deepest sorrow of his life.

He painted her portrait once again from memory, and that picture is quite unlike the others for it is no longer full of glowing life, but daintier, suggestive of a more spiritual life, as if she were growing fragile.

It is written that "from this time, while he did much remarkable work, he seemed like a man on a mountain top, looking on one side to sweet meadows filled with flowers and sunlight, and on the other to a desolate landscape over which a clouded sun is setting." With Saskia died the best of Rembrandt. He made only one more portrait of himself--before this he had made many; and in it he makes himself appear a stern and fateful man. It was after Saskia's death that he painted the "Night Watch," or more properly, "The Sortie."

Rembrandt's home, where he and Saskia were so happy, is still to be seen on a quay of the River Amstel. It is a house of brick and cut stone, four stories high. The vestibule used to have a flag-stone pavement covered with fir-wood. There were also "black-cushioned, Spanish chairs for those who wait," and all about were twenty-four busts and paintings. There was an ante-chamber, very large, with seven Spanish chairs covered with green velvet, and a walnut table covered with "a Tournay cloth"; there was a mirror with an ebony frame, and near by a marble wine-cooler. Upon the wall of this salon were thirty-nine pictures and most of them had beautiful frames. "There were religious scenes, landscapes, architectural sketches, works of Pinas, Brouwer, Lucas van Leyden, and other Dutch masters; sixteen pictures by Rembrandt; and costly paintings by Palma Vecchio, Bassano, and Raphael."

Holland being truly a Protestant country, its artists have given us no great Madonna pictures, although they painted loving, happy Dutch mothers and little babes, but on the whole their subjects are quite different from those of the painters of Italy, France, and Spain.

Rembrandt's studio was different from any other. When he first began to work independently and to have pupils, he fitted it up with many little cells, properly lighted, so that each student might work alone, as he knew far better work could be done in that way. It is said that his pictures of beggars would, by themselves, fill a gallery. He had a kindly sympathy for the poor and unfortunate, and tramps knew this, so that they swarmed about his studio doors, trying to get sittings.

There is a story which doubtless had for its germ a joke regarding the slowness of an errand boy in a friend's household, but which at the same time shows us how rapidly Rembrandt worked. The artist had been carried off to the country to lunch with his friend Jan Six, and as they sat down at the table, Six discovered there was no mustard. He sent his boy, Hans, for it, and as the boy went out, Rembrandt wagered that he could make an etching before the boy got back. Six took the wager, and the artist pulled a copper plate from his pocket - he always carried one - and on its waxed surface began to etch the landscape before him. Just as Hans returned, Rembrandt gleefully handed Six the completed picture.

The Night Watch

The picture generally known as "The Night Watch," but it is really "The Sortie" of a company of musketeers under the command of a standard bearer. Captain Frans Banning-Kock and all his company were to pay Rembrandt for painting their portraits in a group and in action, and they expected to see themselves in heroic and picturesque dress, in the full blaze of day.This picture was called the "Patrouille de Nuit," by the French and the "Night Watch," by Sir Joshua Reynolds because upon its discovery the picture was so dimmed and defaced by time that it was almost indistinguishable and it looked quite like a night scene. After it was cleaned up, it was discovered to represent broad day - a party of archers stepping from a gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight.

The two first personages are Frans Banning-Cocq, Lord of Furmerland and Ilpendam, captain of the company, and his lieutenant, Willem van Ruijtenberg, Lord of Vlaardingen, the two marching side by side. The only figures that are in the light are this lieutenant, dressed in a doublet of buffalo-hide, with gold ornaments, scarf, gorget, and white plume, with high boots. And a girl with blond hair ornamented with pearls, and a yellow satin dress; all the other figures are in the dark, excepting the heads, which are illuminated. By what light? Here is the enigma. Is it the light of the sun? or of the moon? or of the torches? There are gleams of gold and silver, moonlight coloured reflections, fiery lights; personages which, like the girl with blond tresses, seem to shine by a light of their own.... The more you look at it, the more it is alive and glowing; and, even seen only at a glance, it remains forever in the memory, with all its mystery and splendour, like a stupendous vision." Charles Blanc has said: "To tell the truth, this is only a dream of night, and no one can decide what the light is that falls on the groups of figures. It is neither the light of the sun or of the moon, nor does it come from the torches; it is rather the light from the genius of Rembrandt."

The "Night Watch" was painted in 1642 and many of the archer's guild who gave Rembrandt the commission would not pay their share because their faces were not plainly seen. This picture which alone was enough to make him immortal, was the very last commission that any of the guilds were willing to give the artist, because he would not make their portraits beautiful or fine looking to the disadvantage of the whole picture. This work hangs in the Rijks Museum in Amsterdam.

Rembrandt painted more than six hundred and twenty-five pictures and some of them are: "The Anatomy Lesson," "The Syndics of the Cloth Hall," "The Descent from the Cross," "Samson Threatening His Step Father," "The Money Changer," "Holy Family," "The Presentation of Christ in the Temple," "The Marriage of Samson," "The Rape of Ganymede," "Susanna and the Elders," "Manoah's Sacrifice," "The Storm," "The Good Samaritan," "Pilate Washing His Hands," "Ecce Home," and pictures of his wife, Saskia.

Rembrandt lived from 1606 to 1669 and was a pupil of Van Swanenburch.

Who is Who in Rembrandt's painting The Night Watch?

| 01. Captain Frans Banning Cocq 02. Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch 03. Musketeer 04. Ensign bearer, Jan Visscher Cornelissen 05. Sergeant Rombout Kemp 06. Drummer 07. Boy 08. Girl in yellow dress with chicken 09. Musketeer 10. Musketeer 11. Jacob Dircksen de Roy 12. Musketeer 13. Musketeer 14. Musketeer 15. Eldest Musketeer 16. Jung Musketeer 17. Musketeer 18. Musketeer 19. Musketeer 20. Musketeer in conversation with Kemp (05) |  |