History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Santa Klaas and Black Pete

The boy who wanted more cheese

The cat and the cradle

The goblins turned to stone

The golden helmet<

The legend of the wooden shoe

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

The golden helmet

For centuries, more than can be counted on the fingers of both hands, the maidens and mothers of Friesland have worn a helmet of gold covering the crown and back of their heads, and with golden rosettes at each ear. It marks the Frisian girl or woman. She is thus known by this head-dress as belonging to a glorious country, that has never been conquered and is proudly called Free Frisia. It is a relic of the age of gold, when this precious metal was used in a thousand forms, not seen today.

For centuries, more than can be counted on the fingers of both hands, the maidens and mothers of Friesland have worn a helmet of gold covering the crown and back of their heads, and with golden rosettes at each ear. It marks the Frisian girl or woman. She is thus known by this head-dress as belonging to a glorious country, that has never been conquered and is proudly called Free Frisia. It is a relic of the age of gold, when this precious metal was used in a thousand forms, not seen today. Of how and why the golden helmet is worn, this is the story:

In days gone by, when forests covered the land and bears and wolves were plentiful, there were no churches in Friesland. The people were pagans and all worshipped Wodan, whom the Frisians called Fos-i-te'. Certain trees were sacred to him. When a baby was ill, or grown people had a disease, which medicine could not help, they laid the sick one at the foot of the holy tree, hoping for health soon to come. But, should the patient die under the tree, then the sorrowful friends were made glad, if the leaves of the tree fell upon the corpse. It was death to any person who touched the sacred tree with an axe, or made kindling wood, even of its branches.

Now among the wild people of the north, who ate acorns and were clothed in the skins of animals, there came, from the Christian lands of the south, a singer with his harp. Invited to the royal court, he sang sweet songs. To these the king's daughter listened with delight, until the tears, first of sorrow and then of joy, rolled down her lovely cheeks.

This maiden was the pride of her father, because of her sweet temper and willing spirit, while all the people boasted of her beauty. Her eyes were of the color of a sky without clouds. No spring flower could equal the pink and rose in her cheeks. Her lips were like the red coral, which the ship men brought from distant shores. Her long tresses rivalled gold in their glory. And, because her father worshipped Fos-i-te', the god of justice, and his daughter was always so fair to all her playmates, he, in his pride of her, gave her the name Fos-te-di-na, that is, the darling of Fos-i-te', or the Lady of Justice.

The singer from the south sang a new song, and when he played upon his harp his music was apt to be soft and low; sometimes sad, even, and often appealing. It was so much finer, and oh! so different, from what the glee men and harpers in the king's court usually rendered for the listening warriors. Instead of being about fighting and battle, or the hunting of wolves and bears, of stags and the aurochs, it was of healing the sick and helping the weak. In place of battles and the exploits of war lords, in fighting and killing Danes, the harper's whole story was of other things and about gentle people. He sang neither of war, nor of the chase, nor of fighting gods, nor of the storm maidens, that carry up to the sky, and into the hall of Woden, the souls of the slain on the battlefield. The singer sang of the loving Father in Heaven, who sent his dear Son to earth to live and die, that men might be saved. He made music with voice and instrument about love, and hope, and kindness to the sick and poor, of charity to widows and to orphans, and about the delights of doing good. He closed by telling the story of the crown of thorns, how wicked men nailed this good prophet to a cross, and how, when tender-hearted women wept, the Holy Teacher told them not to weep for him, but for themselves and their children. This mighty lord of noble thoughts and words lived what he taught. He showed greatness in the hour of death, by first remembering his mother, and then by forgiving his enemies.

"What! forgive an enemy? Forgive even the Danes? What horrible doctrine do we hear!" cried the men of war. "Let us kill this singer from the south." And they beat their swords on their metal shields, till the clangor was deafening. The great hall rang with echoes of the din, as if for battle. The Druids, or pagan priests, even more angry, applauded the action of the fighting men.

But Fos-te-dÃ-na rushed forward to shield the harper, and her long golden hair covered him.

"No!" said the king to his warriors. "This man is my guest. I invited him and he shall be safe here."

Sullen and bitter in their hearts, both priests and war men left the hall, breathing out revenge and feeling bound to kill the singer. Soon all were quiet in slumber, for the hour was late.

Why were the pagan followers of the king so angry with the singer?

The answer to this question is a story in itself.

Only three days before, a party of Christian Danes had been taken prisoners in the forest. They had come, peaceably and without arms, into the country; for they wanted to tell the Frisians about the new religion, which they had themselves received. In the cold night air, they had, unwittingly, cut off some of the dead branches of a tree sacred to the god Fos-i-te to kindle a fire.

A spy, who had closely watched them, ran and told his chief. Now, the Christian Danes were prisoners and would be given to the hungry wolves to be torn to pieces. That was the law concerning sacrilege against the trees of the gods.

Some of the Frisians had been to Rome, the Eternal City, and had there learned, from the cruel Romans, how to build great enclosures, not of stone but of wood. Here, on holidays, they gave their prisoners of war to the wild beasts, for the amusement of thousands of the people. The Frisians could get no lions or tigers, for these fierce brutes live in hot countries; but they sent hundreds of hunters into the woods for many miles around. These bold fellows drove the deer, bears, wolves, and the aurochs within an ever narrowing circle towards the pits. Into these, dug deep in the ground and covered with branches and leaves, the animals fell down and were hauled out with ropes. The deer were kept for their meat, but the bears and wolves were shut up, in pens, facing the great enclosure. When maddened with hunger, these ravenous beasts of prey were to be let loose on the Christian Danes. Several aurochs, made furious by being goaded with pointed sticks, or pricked by spears, were to rush out and trample the poor victims to death.

The heart of the beautiful Fos-te-di-na, who had heard the songs of the singer of faith in the one God and love for his creatures, was deeply touched. She resolved to set the captives free. Being a king's daughter, she was brave as a man. So, at midnight, calling a trusty maid-servant, she, with a horn lantern, went out secretly to the prison pen. She unbolted the door, and, in the name of their God and hers, she bade the prisoners return to their native land.

How the wolves in their pen did roar, when, on the night breeze, they sniffed the presence of a newcomer! They hoped for food, but got none.

The next morning, when the crowd assembled, but found that they were to be cheated of their bloody sport, they raged and howled. Coming to the king, they demanded his daughter's punishment. The pagan priests declared that the gods had been insulted, and that their anger would fall on the whole tribe, because of the injury done to their sacred tree. The hunters swore they would invade the Danes' land and burn all their churches.

Fos-te-di-na was summoned before the council of the priests, who were to decide on the punishment due her. Being a king's daughter, they could not put her to death by throwing her to the wolves.

Even as the white-bearded high priest spoke, the beautiful girl heard the fierce creatures howling, until her blood curdled, but she was brave and would not recant.

In vain they threatened the maiden, and invoked the wrath of the gods upon her. Bravely she declared that she would suffer, as her Lord did, rather than deny him.

"So be it," cried the high priest. "Your own words are your sentence. You shall wear a crown of thorns."

Fos-te-di-na was dismissed. Then the old men sat long, in brooding over what should be done. They feared the gods, but were afraid, also, to provoke their ruler to wrath. They finally decided that the maiden's life should be spared, but that for a whole day, from sunrise to sunset, she should stand in the market-place, with a crown of sharp thorns pressed down hard upon her head. The crowd should be allowed to revile her for being a Christian and none be punished; but no vile language was to be allowed, or stones or sticks were to be thrown at her.

Fos-te-di-na refused to beg for mercy and bravely faced the ordeal. She dressed herself in white garments, made from the does and fawns - free creatures of the forest - and unbound her golden tresses. Then she walked with a firm step to the centre of the market-place.

"Bring the thorn-crown for the blasphemer of Fos-i-te," cried the high priest.

This given to him, the king's daughter kneeled, and the angry old man, his eyes blazing like fire, pressed the sharp thorns slowly, down and hard, upon the maiden's brow. Quickly the red blood trickled down over her golden hair and face. Then in long, narrow lines of red, the drops fell, until the crimson stains were seen over the back, front, and sides of her white garments.

But without wincing, the brave girl stood up, and all day long, while the crowd howled, in honor of their gods, and rough fellows jeered at her, Fos-te-di-na was silent and patient, like her Great Example. Inwardly, she prayed the Father of all to pardon and forgive. There were not a few who pitied the bleeding maiden wearing the cruel crown, that drew the blood that stained her shining hair and once white clothing.

Years passed by and a great change came over land and people. The very scars on Fos-te-di-na's forehead softened the hearts of the people. Thousands of them heard the words of the good missionaries. Churches arose, on which was seen the shining cross. Idols were abolished and the trees, once sacred to the old gods, were cut down. Meadows, rich with cows, smiled where wolves had roamed. The changes, even in ten years, were like those in a fairy tale. Best of all, a Christian prince from the south, grandson of Charlemagne, fell in love with Fos-te-di-na, now queen of the country. He sought her hand, and won her heart, and the date for the marriage was fixed. It was a great day for Free Frisia. The wedding was to be in a new church, built on the very spot where Fos-te-di-na had stood, in pain and sorrow, when the crown of thorns was pressed upon her brow.

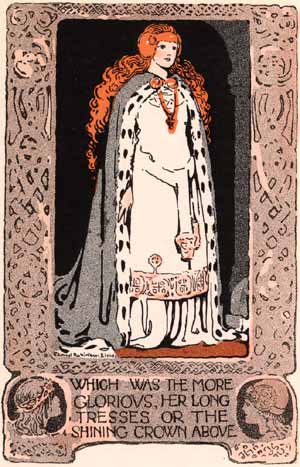

On that morning, a bevy of pretty maidens, all dressed in white, came in procession to the palace. One of them bore in her hands a golden crown, with plates coming down over the forehead and temples. It was made in such a way that, like a helmet, it completely covered and concealed the scars of the sovereign lady. So Fos-te-di-na was married, with the golden helmet on her head. "But which," asked some, "was the more glorious, her long tresses, floating down her back, or the shining crown above it?" Few could be sure in making answer.

Instead of a choir singing hymns, the harper, who had once played in the king's hall, now an older man, had been summoned, with his harp, to sing in solo. In joyous spirits, he rendered into the sweet Frisian tongue, two tributes in song to the crowned and glorified Lord of all.

One praised the young guest at the wedding at Cana, Friend of man, who turned water into wine; the other, "The Great Captain of our Salvation," who, in full manly strength, suffered, thorn-crowned, for us all.

Then the solemn silence, that followed the song, was broken by the bride's coming out of the church. Though by herself alone, without adornment, Fos-te-di-na was a vision of beauty. Her head-covering looked so pretty, and the golden helmet was so becoming, that other maidens, also, when betrothed, wished to wear it. It became the fashion-for Christian brides, on their wedding days, to put on this glorified crown of thorns.

All the jewelers approved of the new bridal head-dress, and in time this golden ornament was worn in Friesland every day. Thus it has come to pass that the Frisian helmet, which is the glorified crown of thorns, is, in one form or another, worn even in our day. When Fos-te-di-na's first child, a boy, was born, the happy parents named him William, which is only another word for Gild Helm. Out from this northern region, and into all the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands, the custom spread. In one way or another, one can discern, in the headdresses or costumes of the Dutch and Flemish women, the relics of ancient history.