History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch portrait painters

Frans Hals (1584-1666)<

Rembrandt van Ryn (1606-1669)

Dutch genre painters

Dutch landscape painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

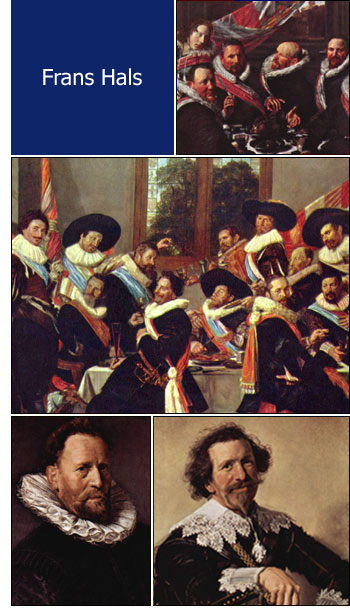

Frans Hals (1584-1666)

Frans Hals (1584- 1666) came from an old burgher family of Haarlem, the archives mentioning the family name for two centuries before his birth. Through the stress of the times his parents had left the city some time after it was taken by the Spaniards, and Frans was born while they were in exile in Antwerp.

Frans Hals (1584- 1666) came from an old burgher family of Haarlem, the archives mentioning the family name for two centuries before his birth. Through the stress of the times his parents had left the city some time after it was taken by the Spaniards, and Frans was born while they were in exile in Antwerp.Little is known of his early years. Since the family returned to Haarlem when Frans was about twenty years, he may have received some training in the rudiments of his art in the Flemish city. Not a trace of this is visible, not even in his first known work, dated 1614, a portrait of Johannes Bogardus. It is, however, more plausible to assume that these early years were practically wasted, that the unsettled condition of the family as refugees, constantly waiting to return home, had its effect on the young man in preventing him to prepare himself for any lifeÂwork, and that evil associations may have led him into habits which later developed to a regretful irregularity of life.

It is more likely that his natural bent was only heeded when, on their return to Haarlem, Frans entered the studio of Karel van Mander; a mediocre painter who occupied himself also with writing on Art.

The work of Hals of his first ten years is entirely lost. It must have been of brilliant promise, for in 1616 he had received already the important commission to paint "The Twelve Officers of the Archers of Saint George,". It shows thus early the mastery of his craft, and those individual traits only to be found with one who was born great. The same year we find him summoned before the magistrates on the charge of "mishandling" his wife, whom he had married some six years before. His drunken habits were the basis of the reprimand he received. His wife died soon afterwards, and he found a more congenial companion in his second venture into matrimony with Lysbeth Reyniers. Since they lived together for nearly fifty years we must suppose that she made allowance for his habits and tactfully restrained him from too many excesses. There seems to be perfect good-fellowship between them in that portrait of himself and Lysbeth which hangs in the Amsterdam Ryksmuseum.

The accounts of his dissolute ways are as usual much exaggerated. That Hals was intemperate and improvident must be conceded, but no mere wine-bibbing sot, as he has been called, could have been granted association with the best citizens of his town, nor could he have produced the masterÂworks which have raised their author on such a high pedestal in the hall of fame.

Unfortunately his art soon lost its hold upon the people, and although Hals received commissions to the last, these were ill-paid, and this, coupled with his manner of life, brought him into dire financial straits. The city council provided for him, from 1662 to his death, with a pension of two hundred Carolus guilders, a considerable sum for these times.

While Rembrandt surpassed Hals only in one respect - in the romanticism of his light-effects - Hals was his equal in every quality which goes to make a master of masters. No man has ever surpassed the Haarlem genius as a technician. The manner of painting, like execution in music, is of the greatest importance. The manner of Hals was bold, imperial, its power subdued and graded according to the importance of the parts; but above all of an ease and assurance, without correction or emendation, that verges on the miraculous. There was progress even in his magical touch, whereby the sparkling virtuosity of his earlier years developed towards greater refinement, harmony, and sobriety in his latest paintings, expressing himself ever more concisely and yet more clearly.

The vitality, the frankly human side of his portraits, strike us because the character of his sitters has been apparently recognized without searching, keenly caught on the self-revealing instant, and transmitted to the canvas so that it pulsates with life - life itself. Yet, no vulgar trickery for illusianary deceit anything but that. His work is frankly painting. His portrait is a painted man or woman. But herein becomes Hals the superior of all rivals, the inimitable marvel that, while we see his broad dabs and dashes and count the strokes that go to make mustachios or beard - still the person appears in his ego, with the laugh or smile that reveals the soul.

Nor is he a whit less wonderful in his composition, another important factor in painting. Every writer on Hals, as far as I know, has regarded composition as his weakest point. Unjustly so. Composition is not only the arrangement of subordinate parts towards one focal centre. It may also mean the arrangement of various parts, which by equal lighting have become of equal importance, in such a manner that, when viewed at the distance when the whole may be seen at one glance, there is a perfect equilibrium, a graceful arrangement of the primary spots to an amalgamated and unified whole. In this manner of composition Hals was supreme. Look at his archers pieces in Haarlem. True, each individual could be taken out and studied in detail, yet each is needed in the combination. And these men did not just happen to stand and sit and act the way they do - it only seems so. The artist arranged and composed them, and the artlessness of his seemingly unconscious grouping reveals "the art that hides art."

Even with his lack of aerial perspective, whereby all figures of his group pieces seem to be principal, their co-relation, their harmonious arrangement, and the subjection or elaboration of detail create what in music is called melody. And his colour is supreme. He touched a rich and ever more mellow palette with his brush as with a magician's wand, and improvised, created his chromatic scale with subtle intensity. How colour can speak he showed in his flat painting, from which Manet and Whistler drew their inspiration. How colour can model, aye sculpture, he showed in his tones and values. Here he dashes a full-loaded brush, there he flows his colour in smooth tints along the folds of gown or collaret, but always with a superb freedom and breadth that is kept perfectly in control and subordinates his richest masses with the greatest delicacy to the flesh tones. His colour has never that mosaic or, marquetry look of his modern imitators.

His lighting is uniform and evenly distributed, a subdued daylight that did not affect the harmonious assertion of each shade. Only for a few years, between 1635 and 1642, he seems to have been somewhat under Rembrandt's influence, as may be seen in the group piece in Haarlem, painted in 1641, and in "The Lean Company" in the Ryksmuseum. He only experimented, however, during these years with the new idea of chiaroscuro, for the archers piece of St. Joris, painted in 1639, has no Rembrandtesque qualities. To the end he adhered to his own conception of the light problem, which ignored the possibilities, of strong contrast, and he was satisfied to use light, well tempered and diffused.

The narrowness of his field of labour, which confined itself exclusively to portraiture, including the portraits of types, as "The Jolly Man," "Hille Hobbe", and "The Jester," was of his own choice. He did not lack imagination to produce genre, so called. But his time was sufficiently occupied with the commissions that came to him to satisfy the good-natured bohemian, not burdened with any averweaning anxiety to drain his vitality by excessive labour. If rest is the means to recuperate strength, he must have rested a great deal to enable him to keep an working with scarcely diminishing power until past eighty.

The neglect in which he fell during his later years continued for generations, when he was scarcely deemed worthy of honour. As late as 1852 the "Portrait of Himself and Wife" in the Ryksmuseum brought at the Six van Hillegom Sale only $240. But then the tide turned. Public recognition, has now accorded him his true place among the foremost painters of the world, one who justly fills the second place in the glorious galaxy of the Masters of the 17th Century Dutch School.