History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch portrait painters

Frans Hals (1584-1666)

Rembrandt van Ryn (1606-1669)<

Dutch genre painters

Dutch landscape painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

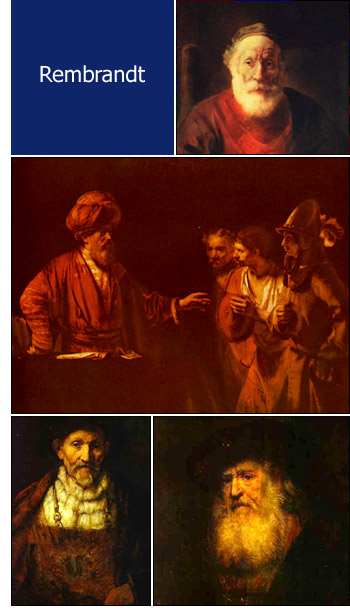

Rembrandt van Ryn (1606-1669)

The "King of Painters" stands supreme in the School of the Netherlands, excelled by none, equalled by only a few of the masters of other times and countries. He was one of the heroes of Art, a genius, at once Dutch and universal, belonging to the 20th as to the 17th century.

The "King of Painters" stands supreme in the School of the Netherlands, excelled by none, equalled by only a few of the masters of other times and countries. He was one of the heroes of Art, a genius, at once Dutch and universal, belonging to the 20th as to the 17th century.The prodigality of his power was developed by painful study and the laborious acquisition of knowledge. He was always keen to know what men had done before him, as we may see from his large collection of the drawings of Durer, Cranach, Lukas van Leiden, Marc Antonio, Mantegna, and others, which he bought for use as well as for the love of beautiful things. And he profited by their teaching, as evidenced in some of his works, paintings and etchings. But after acquiring knowledge he trifled with it afterwards and became the most original of painters, creating out of all the technics available to him one peculiarly his own.

While he was not the first to enter into the secret of the marvellous effect of light and shade for same of his forerunners had already essayed this problem of chiaroscuro, Rembrandt was the first to develop to perfection the concentration of light and the diffusion of luminosity from the deepest shade. In this he became the inspirer, not only of his pupils and of his contemporaries, but of all pictorial art that came after. His method became a new direction in art expression and must be regarded the characteristic feature of the Dutch school as it now gradually developed. These painters, were the first and always remained the foremast to depict "the poetry of chiaroscuro."

Rembrandt's life (1606-1669), like his pictures, shows strong contrasts of light and shade, with the dark predominating; for which his early biographers would hold himself mainly responsible. It is amazing that in the light of recent researches those old stories to the master's detriment are still revamped.

Let us pass to the indisputable biographical data as they may be collated from various sources. Rembrandt Harmensz van Ryn was born an the 15th of July, 1606, not in his father's mill, as was used to tell, but in the comfortable dwelling in the Weddesteeg near the Wittepoart of the city of Leyden, as Vosmaer has discovered. His parents, Harmen Gerritsz van Ryn and Neeltjen Willems van Zuitbroeck, were well-to-do, and when young Rembrandt was thirteen years old he was sent to the preparatory school (now called the Gymnasium) of the Leyden University. But the youth did not take kindly to classical studies - in fact he never was much of a reader except of his Bible. In the inventory of his possessions, taken in after life, besides this well-worn Bible, only fifteen books are noted.

His artistic bent found training in the studio of Jacob van Swanenburgh, a local painter of whom little else is known, where for three years he learned the elements of his profession. At the age of seventeen we find him in Amsterdam with Pieter Lastman, who had studied in Italy and had felt the influence of Caravaggio and of Elsheimer. Some of Lastman's pictures offer contrasts of light and shade which seem to foreshade the great works of his pupil. But Rembrandt stayed only six months with this teacher, as he did not find any advantage to be gained, his work then already outÂstripping that of his master.

He returned to Leyden, and using the members of his family for models he equipped himself fully to accept commissions for portraits, which soon came to him. His earliest known picture, a "Paul in Prison," is dated 1627. He refused to go to Italy as advised, disclaiming any desire to follow in the ruts of his predecessors, and already conscious of his individual power. As early as 1628 he received his first pupil, Gerard Dou, a lad of fifteen.

To widen the scope of his opportunities Rembrandt returned in 1630 to Amsterdam, and in the next year completed his well-known "Simeon in the Temple," now in the Mauritshuis, which at once proclaimed his large conception of complicated compositions. A slight change in the studyÂheads and portraits of this time shows that he had become acquainted with the work of Thomas de Keyser. His reputation became, however, fully established by that marvellous creation, "The Anatomy Lesson of Prof. Nicolaes Tulp" - a wonderful performance for a young man of twentyÂsix. Twice before a scene from the dissectingÂroom had been attempted for Surgeons' Guilds by Aert Pietersz of Haarlem: in 1601, and by Pieter Mierevelt in 1616.

Although Rembrandt must have known these compositions, his presentation of Prof. Tulp's Lesson indicates that vital point which distinguishes his group paintings, guild or militia pieces, above like compositions by all other masters of his time. The latter present in these groups frank portraits, often leading to division of interest, no matter how skilfully arranged, the portraiture being the primary motive. With Rembrandt we always find, together with the portraiture, a vital scenic presentation in which all members bear an harmonious part.

Rembrandt had taken up his abode in Amsterdam with Hendrik van Uylenborch, a painter and dealer in works of art, where that passion of collecting was aroused which was to be the cause of all Rembrandt's financial misfortunes in after life. There he met van Uylenbarch's cousin, Saskia, a young girl from Friesland, an orphan who was temporarily staying with another relative, Dominee Sylvius.

In June, 1634, they were married and the happiest years of the painter's life followed. There were no clouds an the horizon. His income was large for those times. He was a most industrious worker, then painting forty pictures in a year. For his half-length portraits he received five hundred guilders, for his scriptural subjects as much as 1,200 guilders. For the "Night Watch" he was paid 1,600 guilders. In those years of his married life his annual income must have been from 12,000 to 15,000 guilders. To this must be added Saskia's dowry of 40,000 guilders, and various legacies from his mother and from several of Saskia's relatives. But that he lived freely is shown when at Saskia's death, after eight years, their joint property amounted to only 40,750 guilders, his possessions consisting principally of jewelry, art objects, and collections of drawing and engravings. The house in which they had moved on the St. Antanie Breestraat was not paid for, and various sums of borrowed money, carelessly neglected by the artist for the sake of adding to his collections, ominously foreshaded the dire fatality.

During these happy years the master's work is signalized by its richness of colour, the dramatic action of the figures, and the perfection of his light painting. From, 1633 to 1639 he completed the "Passion Series," the various Saskia portraits, and several of himself, the "Samson Propounding the Riddle at the Wedding Feast" and "The Good Samaritan". In 1640-1642, the last of these joyful years of his wedded life, he wrought several magnificent portraits, notably "The Gilder," a portrait of Paulus Doomer and the "Night Watch." These were also the years of greatest popularity, when the leading citizens of Amsterdam vied with each other to receive him.

Among his friends were counted the Secretary of the Stadhouder, Constantin Huygens, a poet and scientist; the Mennonite preacher Renier Anslo; the Rabbi Manasseh ben Israel; the Burgomaster Jan Six, who received him frequently at his country seat at Hillegom; the Collector of Revenue Uyttenbogaert; the goldsmith Janus Lutina; the Burgomaster Cornelis Witzen, and many others.

Three children Saskia bore him died in infancy, but in September, 1641, Titus was born, who lived to manhood. The thirty-year old mother, however, died the next Summermonth, and with her departed all Rembrandt's joy of life. Saskia in her will left all her property to Titus, subject to Rembrandt's use during his life or so long as he remained unmarried. Why Saskia made this peculiar provision, which was not altogether customary in those times, we know not. But it had a portentous bearing and proved of serious consequences later on. Rembrandt, in his sorrow, devoted himself exclusively to his art. Many of his most beautiful scriptural subjects, with spiritual depth, date from these years. He also added landscape to the subjects of his painting and etching.

The years which followed, from 1642 until the time when Rembrandt was declared a bankrupt in 1656, have furnished most of the tales derogatory to his character. It must, however, be borne in mind that with all the moral correctness of public opinion as to social doings, the friends we have enumerated above did not forsake him, many helping him financially to stave off the insolvency proceedings. The Six family, then one of the most prominent in Amsterdam, always remained loyal to him, for the famous portrait of Jan Six must, according to Vosmaer, be placed in 1656, or according to Michel and Bode in 1660. These friends would not have remained with him had there been any truth in the tales which are to this day mongered.

Something occurred in 1649 which tested their loyalty and which is the basis of many of the evil reports. When Saskia died, leaving him with the few months old baby, Rembrandt had as housekeeper in his large house in the Breestraat a woman of uncertain temper, Geertge Dirx, the widow of a trumpeter. She must have been warmly attached to young Titus, for in 1648 she made her will in favour of her charge. But in the following year she left Rembrandt's service, most probably on account of jealousy of Hendrickje Stoffels. This young woman had some time before come as her assistant in Rembrandt's household. We know her features well from various portraits the master painted. These features are pleasant, with gentle eyes, and a modest womanliness of character.

After Geertge Dirx left the house Rembrandt desired to protect his child Titus as to the disposition she had made of her property, and voluntarily settled an annuity of 60 guilders on her, paying her also 150 guilders in hand, an condition that she should not alter her will. It was an unwise move as to further developments, for the woman shortly afterwards accused him of illicit intercourse with her and of a breach of promise to marry. Rembrandt stoutly denied the accusation, but his voluntary pecuniary settlement upon her weighed against him before the "Commissionaries of Marriage Affairs," and they condemned the painter to pay Geertge 200 guilders instead of 60 guilders per annum. The indignation of the master knew no bounds, and in his passionate resentment of the injustice done him he assumed the very relations with Hendrickje Stoffels of which he had been unjustly accused by Geertge. Unjustly, for Geertge's unreliability is shown by the fact that in the following year she had to be placed in a madhouse at Gouda, where she died shortly afterwards.

Rembrandt's relations with Hendrickje must have been sufficiently discreet not to arouse the estrangement of his friends, while much later, in his declining years, they were regarded by their neighbours on the Rozengracht as lawfully wedded, and Titus always treated her with affection as his second mother. No record of a marriage is, however, in existence. That Hendrickje was constrained by a sincere love for the master may be seen in her faithful care for him to the time of her death, and in the public reproach she was willing to bear, when in 1654 she, was three times cited to appear before the Church Council for living incontinently with Rembrandt, was publicly reproved, and excluded from partaking of the Lord's Supper. It is here to be noted that Rembrandt was also cited, but only the first time and apparently by mistake, so that we may presume that he did not belong to the State Church, but more likely to the Mennonite congregation.

A child by Hendrickje was buried on August 15, 1652, but on October 30, 1654, another child was baptized which received the name of Cornelia, after the master's mother. Cornelia, same years after her father's death, married a painter named Suythoff, with whom she emigrated to the East Indies, where in 1678 her first son was baptized with the name of Rembrandt.

There is no doubt that Rembrandt would have married Hendrickje had it not been for the clause in Saskia's will. This would have compelled him to pay the principal of her legacy in full to the guardians of his son Titus. He was no longer able to do this, as his finances were becoming more and more involved. And finally the storm brake. Money-lenders and the holder of the mortgage on the Breestraat house became insistent. During these years Rembrandt strained all his powers to stay off the inevitable, executing an unusually large number of pictures and etchings, which include several important works, among others "Professor Deyman's Anatomy Lesson." But all his income went to pay the interest an his many debts, barely leaving him living expenses, and at last he was declared bankrupt in 1656; an inventory was taken, all his possessions were sold for something under 5,000 guilders, and his house for 11,218 guilders.

It appears that all that was left to Rembrandt were the plates of his etchings and his painter's materials. After moving about from place to place, we find him at last in a modest little house an the Rozengracht. For a time his position seems to have somewhat improved. Hendrickje and Titus formed a partnership to deal in works of art, employing Rembrandt as expert and adviser, for which they were to give him board and lodging. It was a disinterested scheme to save to the master some of his earnings, which were legally impounded for the payment of his ancient debts. Titus went from door to door selling his father's etchings, which probably brought in most of the earnings of the humble firm. It was not an instance of Rembrandt's avarice, as Houbraken puts it, but proof of the son's devotion which lightened the master's declining years. That this love surrounding him caused the flame of genius to burn again brighter we see in the marvellous portrait group of the "Staalmeesters," the Syndics of the Drapers' Guild, which Rembrandt painted in 1662.

There is an old tradition that Rembrandt visited England in 1661, but the slight evidence in support of this cannot weigh against the improbability that in the straitened circumstances of that time he would also have overcome his aversion to travel.

Read more information about Rembrandt van Rijn.