History of Holland

History of HollandHistory of Netherlands

Amsterdam Holland

Netherlands cities

Tulips of Holland

Dutch painters

Dutch writers and scientists

Dutch paintings

Frans Hals

Hobbema

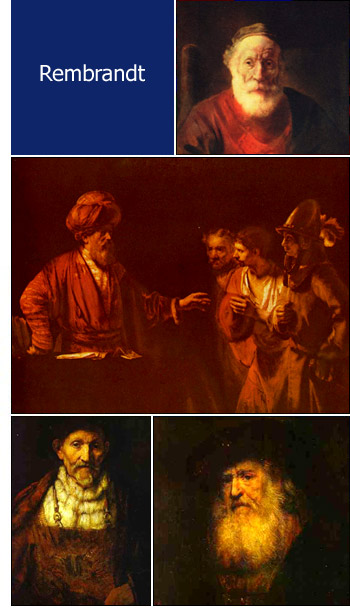

Rembrandt van Rijn<

Famous Dutch people

Dutch history

Dutch folk tales

Rembrandt and the Nightwatch

Holland history

Holland on sea history

Pictures of Holland

Dutch architecture

Holland facts

New Amsterdam history (New York)

Useful information

Rembrandt van Rijn

The Netherlands had belonged in the 15th century to the Dukes of Burgundy. Through the marriage of the only daughter of the last Duke, these territories passed into the possession of the King of Spain, who remained a Catholic, whilst the northern portion of the Netherlands became sturdily Protestant. Their struggle, under the leadership of William the Silent, against the yoke of Spain, is one of the stirring pages of history. By the beginning of the 17th century, seven of the northern states of the Netherlands, of which Holland was the chief, had emerged as practically independent. The southern portion of the Netherlands, including the old province of Flanders, remained Catholic and was governed by a Spanish Prince who held his court at Brussels.

The Netherlands had belonged in the 15th century to the Dukes of Burgundy. Through the marriage of the only daughter of the last Duke, these territories passed into the possession of the King of Spain, who remained a Catholic, whilst the northern portion of the Netherlands became sturdily Protestant. Their struggle, under the leadership of William the Silent, against the yoke of Spain, is one of the stirring pages of history. By the beginning of the 17th century, seven of the northern states of the Netherlands, of which Holland was the chief, had emerged as practically independent. The southern portion of the Netherlands, including the old province of Flanders, remained Catholic and was governed by a Spanish Prince who held his court at Brussels.When peace came at last, there was a remarkable outburst of painting in each of the two countries. Rubens was the master painter in Flanders. In Holland there was a yet more wide-spread activity. Indomitable perseverance had been needed for so small a country to throw off the rule of a great power like Spain. The long struggle seems to have called into being a kindred spirit manifesting itself in every branch of the national life. Dutch merchants, Dutch fishermen, and Dutch colonizers made themselves felt as a force throughout the world. The spirit by which Dutchmen achieved political success was pre-eminent in the qualities which brought them to the front rank in art. There were literally hundreds of painters in Holland, few of them bad.

That does not mean that all Dutchmen had the magical power of vision belonging to the greatest artists, the power that transforms the objects of daily view into things of rare beauty, or the imagination of a Tintoret that creates and depicts scenes undreamt of before by man. Many painted the things around them as they looked to a commonplace mind, with no glamour and no transforming touch. When we see their pictures, our eyes are not opened to new effects. We continue to see and to feel as we did before, but we admire the honest work, the pleasant colour, and the efficiency of the painters. In default of Raphaels, Giorgiones, and Titians, we should be pleased to hang upon our walls works such as those. But towering above the other artists of Holland, great and small, was one Dutchman, Rembrandt, who holds his own with the greatest of the world.

He was born in 1606, the son of a miller at Leyden, who gave him the best teaching there to be had. Soon he became a good painter of likenesses, and orders for portraits began to stream in upon him from the citizens of his native town. These he executed well, but his heart was not wrapped up in the portrayal of character as John Van Eyck's had been. Neither was it in the drawing of delicate and beautiful lines that he wished to excel, as did Holbein and Raphael. He was the dramatist of painting, a man who would rather paint some one person ten times over in the character of somebody else, high priest, king, warrior, or buffoon, than once thoroughly in his own. But when people ordered portraits of themselves they wanted good likenesses, and Rembrandt was happy to supply them. At first it was only when he was working at home to please himself that he indulged his picturesque gift. He painted his father, his mother, and himself over and over again, but in each picture he tried some experiment with expression, or a new pose, or a strange effect of lighting, transforming the general aspect of the original. His own face did as well as any other to experiment with; none could be offended with the result, and it was always to be had without paying a model's price for the sitting. Thus all through his life, from twenty-two to sixty-three, we can follow the growth of his art with the transformation of his body, in the long series of pictures of his single self.

More than any artist that had gone before him, Rembrandt was fascinated by the problem of light. The brightest patch of white on a canvas will look black if you hold it up against the sky. How, then, can the fire of sunshine be depicted at all? Experience shows that it can only be suggested by contrast with shadows almost black. But absolutely black shadows would not be beautiful. Fancy a picture in which the shadows were as black as well-polished boots! Rembrandt had to find out how to make his dark shadows rich, and how to make a picture, in which shadow predominated, a beautiful thing in itself, a thing that would decorate a wall as well as depict the chosen subject. That was no easy problem, and he had to solve it for himself. It was his life's work. He applied his new idea in the painting of portraits and in subject pictures, chiefly illustrative of dramatic incidents in Bible history, for the same quality in him that made him love the flare of light, made him also love the dramatic in life.

Rembrandt's mother was a Protestant, who brought up her son with a thorough knowledge of the Scripture stories, and it was the Bible that remained to the end of his life one of the few books he had in his house. The dramatic situations that he loved were there in plenty. Over and over again he painted the Nativity of Christ. Sometimes the Baby is in a tiny Dutch cradle with its face just peeping out, and the shepherds adoring it by candle-light. Often he painted scenes from the Old Testament; such as Isaac blessing Esau and Jacob, who are shown as two little Dutch children. Simeon receiving the Infant Christ in the Temple is a favourite subject, because of the varied effects that could be produced by the gloom of the church and the light on the figure of the High Priest. These, and many other beautiful pictures, were studies painted for the increase of the artist's own knowledge, not orders from citizens of Leyden, or of Amsterdam, to which capital he moved in 1630. At the same time he was coming more and more into demand as a portrait-painter. These were days in which he made money fast, and spent it faster. He had a craving to surround himself with beautiful works of art and beautiful objects of all kinds that should take him away from the dunes and canals into a world of romance within his own house.

He disliked the stiff Dutch clothes and the great starched white ruffs worn by the women of the day. He had to paint them in his portraits; but when he painted his beautiful wife, Saskia, she is decked in embroideries and soft shimmering stuffs. Wonderful clasps and brooches fasten her clothes. Her hair is dressed with gold chains, and great strings of pearls hang from her neck and arms. Rembrandt makes the light sparkle on the diamonds and glimmer on the pearls. Sometimes he adorns her with flowers and paints her as Flora. Again, she is fastening a jewel in her hair, and Rembrandt himself stands by with a rope of pearls for her to don. All these jewels and rich materials belonged to him. He also bought antique marbles, pictures by Giorgione and Titian, engravings by Dürer, and four volumes of Raphael's drawings, besides many other beautiful works of art.

These were splendid years, years in which he was valued by his contemporaries for the work he did for them, and years in which every picture he painted for himself gave him fresh experience. A picture of the anatomy class of a famous physician had been among the first with which Rembrandt made a great public success. Every face in it—and there were eight living faces—was a masterpiece of portraiture, and all were fitly grouped and united in the rapt attention with which they followed the demonstration of their teacher.

In 1642 he received an order to paint a large picture of one of the companies of the City Guard of Amsterdam. According to the custom of the day, each person portrayed in the picture contributed his equal share towards the cost of the whole, and in return expected his place in it to be as conspicuous as that of anybody else. Such groups were common in Holland in the seventeenth century. The towns were proud of their newly won liberties, and the town dignitaries liked to see themselves painted in a group to perpetuate remembrance of their tenure of office. But Rembrandt knew that it was inartistic to give each and every person in a large group an equal or nearly equal prominence, although such was the custom to which even Franz Hals' brush had yielded full compliance. For his magnificent picture of the City Guard, Rembrandt chose the moment when the drums had just been sounded as an order for the men to form into line behind their chief officers' march-forth. They are coming out from a dark building into the full sunshine of the street.

All in a bustle, some look at their fire-arms, some lift their lances, and some cock their guns. The sunshine falls full upon the captain and the lieutenant beside him, but the background is so dark that several of the seventeen figures are almost lost to view. A few of the heads are turned in such a way that only half the face is seen, and no doubt as likenesses some of them were deficient. Rembrandt was not thinking of the seventeen men individually. He conceived the picture as a whole, with its strong light and shade, the picturesque crossing lines of the lances, and the natural array of the figures. By wiseacres, the picture was said to represent a scene at night, lit by torch-light, and was actually called the 'Night Watch,' though the shadow of the captain's hand is of the size of the hand itself, and not greater, being cast by the sun. Later generations have valued it as one of the unsurpassed pictures in the world; but it is said that contemporary Dutch feeling waxed high against Rembrandt for having dealt in this supremely artistic manner with an order for seventeen portraits, and that he suffered severely in consequence. Certainly he had fewer orders. The prosperous class abandoned him. His pictures remained unsold, and his revenue dwindled.

Rembrandt was thirty-six years of age and at the very height of his powers, at the time of the failure of this his greatest picture. His mature style of painting continued to displease his contemporaries, who preferred the work of less innovating artists who painted good likenesses smoothly. Every year his treatment became rougher and bolder. He transformed portraits of stolid Dutch burgomasters into pictures of fantastic beauty; but the likeness suffered, and the burgomasters were dissatisfied. Their conservative taste preferred the smooth surface and minute treatment of detail which had been traditional in the Low Countries since the days of the Van Eycks. Year after year more of their patronage was transferred to other painters, who pandered to their preferences and had less of the genius that forced Rembrandt to work out his own ideal, whether it brought him prosperity or ruin. These painters flourished, while Rembrandt sank into ever greater disrepute.

It is certain, too, that he had been almost childishly reckless in expenditure on artistic and beautiful things which were unnecessary to his art and beyond his means, although those for a while had been abundant. At the time of the failure of the 'Night Watch,' his wife Saskia died, leaving him their little son, Titus, a beautiful child. Through ever-darkening days, for the next fifteen years, he continued to paint with increasing power. It is to this later period that our picture of the 'Man in Armour' belongs.

Rembrandt was a typical Dutch worker all his life. Besides the great number of pictures that have come down to us, we have about three thousand of his drawings, and his etchings are very numerous and fine.

There are, broadly speaking, two different processes. You can take a block of wood and cut away the substance around the lines of the design. Then when you cover with ink the raised surface of wood that is left and press the paper upon it, the design prints off in black where the ink is but the paper remains white where the hollows are. This is the method called wood-cutting, which is still in use for book illustrations.

In the other process, the design is ploughed into a metal plate, the lines being made deep enough to hold ink, and varying in width according to the strength desired in the print. You then fill the grooves with ink, wiping the flat surface clean, so that when the paper is pressed against the plate and into the furrows, the lines print black, out of the furrows, and the rest remains white.

There are several ways of making these furrows in a metal plate, but the chief are two. The first is to plough into the metal with a sharp steel instrument called a burin. The second is to bite them out with an acid. This is the process of etching with which Rembrandt did his matchless work. He varnished a copper plate with black varnish. With a needle he scratched upon it his design, which looked light where the needle had revealed the copper. Then the whole plate was put into a bath of acid, which ate away the metal, and so bit into the lines, but had no effect upon the varnish. When he wanted the lines to be blacker in certain places, he had to varnish the whole rest of the plate again, and put it back into the bath of acid. The lines that had been subjected to the second biting were deeper than those that had been bitten only once.

The number of plates etched by Rembrandt was great, at least two hundred; some say four hundred. Their subjects are very various—momentary impressions of picturesque figures, Scriptural scenes, portraits, groups of common people, landscapes, and whatever happened to engage the artist's fancy, for an etching can be very quickly done, and is well suited to record a fleeting impression. Thousands of the prints still exist, and even some of the original plates in a very worn-down condition.

In spite of the quantity and quality of Rembrandt's work, he was unable to recover his prosperity. He had moved into a fine house when he married Saskia, and was never able to pay off the debts contracted at that time. Things went from bad to worse, until at last, in 1656, when Rembrandt was fifty, he was declared bankrupt, and everything he possessed in the world was sold. We have an inventory of the gorgeous pictures, the armour, the sculptures, and the jewels and dresses that had belonged to Saskia. His son Titus retained a little of his mother's money, and set up as an art dealer in order to help his father.

It is a truly dreary scene, yet Rembrandt still continued to paint, because painting was to him the very breath of life. He painted Titus over and over again looking like a young prince. In these later years the portraits of himself increase in number, as if because of the lack of other models. When we see him old, haggard, and poor in his worn brown painting-clothes, it hardly seems possible that he can be the same Rembrandt as the gay, frolicking man in a plumed hat, holding out the pearls for Saskia.

In his old age he received one more large order from a group of six drapers of Amsterdam for their portraits. It has been said that the lesson of the miscalled 'Night Watch' had been branded into his soul by misfortune. What is certain is that, while in this picture he purposely returned to the triumphs of portraiture of his youth, he did not give up the artistic ideals of his middle life. He gave his sitters an equal importance in position and lighting, and at the same time painted a picture artistically satisfying. Not one of the six men could have had any fault to find with the way in which he was portrayed. Each looks equally prominent in vivid life. Yet they are not a row of six individual men, but an organic group held together you hardly know how. At last you realize that all but one are looking at you. You are the unifying centre that brings the whole picture together, the bond without which, metaphorically speaking, it would fall to pieces.

This picture of six men in plain black clothes and black hats, sitting around a table, is by some considered the culmination of Rembrandt's art. It shows that, in spite of misfortune and failure, his ardour for new artistic achievement remained with him to the end.

In 1662 Rembrandt seems to have paid a brief and unnoticed visit to England. If Charles II. had heard of him and made him his court painter, we might have had an unrivalled series of portraits of court beauties by his hand instead of by that of Sir Peter Lely. As it was, a hasty sketch of old St. Paul's Cathedral, four years before it was burnt down, is the sole trace left of his visit.

The story of his old age is dreary. Even Titus died a few months before his father, leaving him alone in the world. In the autumn of 1669 he himself passed away, leaving behind him his painting-clothes, his paint-brushes, and nothing else, save a name destined to an immortality which his contemporaries little foresaw. All else had gone: his wife, his child, his treasures, and his early vogue among the Dutchmen of his time.

The last picture of all was a portrait of himself, in the same attitude as his first, but disillusioned and tragic, with furrowed lines and white hair. No one cared whether he died or not, and it is recorded that after his death pictures by him could be bought for sixpence. Thus ended the life of one of the world's supremely great painters.

Read more information about Rembrandt.